Travelling around Norway in the Spring is a fantastic experience. During my trip in 2013, we hooked up with the key movers and shakers involved in forming the country’s house and disco scenes. I was lucky enough to touch down in Oslo, Bergen and Tromsø, and many weird and beautiful places in the surrounding areas. I travelled with Ben Davis, who was directing the film we were working on, formed from interviews with the key people from the dance scene plus Paper Recording’s label artists such as Those Norwegians. We were also curious about the country, geography, and people and how they influenced each other’s creative passions. This film’s working title was ‘Northern Disco Lights – The Rise and Rise of Norwegian House Music’. During our visit, we spoke to as many DJs, producers, promoters and radio stations as possible and decided to publish these best bits that sum up the trip, the film and our findings.

Rune Lindbæk was a key participant in the Tromsø music community in the late eighties and nineties who has worked with Röyksopp, Those Norwegians and is a successful international DJ.

What was it like growing up in Tromsø in the seventies?

Growing up in Tromsø in the seventies was very safe. Society was changing because in 1970 when I was born, Norway started to extract oil and gas from the sea, becoming a solid foundation for our society to grow. Geographically, it is an outpost to the Arctic. But it is the most northerly university town in the world and our influences come from all over the world. It’s a very international city with so much going on, which you just wouldn’t expect from a city with a population of only 70,000.

What music were you listening to growing up?

The big influence for me was Boney M’s ‘Night Flight to Venus’ album and ABBA my mum liked to listen to disco music. A friend’s big brother had ‘Man Machine’ by Kraftwerk and it changed my life completely. I thought it was really cool and very scary. I thought Kraftwerk were some of the scariest things I’d ever heard, but it was addictive. At the time, in Norway, there were no rhythms, it wasn’t like living in the Bronx [New York, US] hearing beats and rhythms all around you. The only music we heard was played on our national radio station which would have been something like the Carpenters, and other ‘nice’ music. I do really like the Carpenters because it reminds me of those days but there were certainly no rhythms in Norway! I started checking out AM Radio and built an AM receiver in my bedroom that had a 20-metre cable running out of my window to our neighbour’s tree, just to try and listen to music from Radio Luxembourg. Nowadays you can have all the songs in the world in seconds.

When did you start hearing [rhythmic] dance music?

Well, when my mum came home with cassettes of disco compilations like labels like K-Tel [from the UK], and Grandmaster Flash on the Wheels of Steel, which Danish next-door neighbour came home back from Denmark with one day, I absolutely loved it. My mum had a very bad quality turntable and I tried to scratch with the Grandmaster Flash record to mess around with the bass and the treble and really enjoyed it. Whenever a similar track sneaked into our charts, there was that rhythm again, I loved it. When I heard ‘Blue Monday’ by New Order, it was the coolest thing I’ve heard in my life.

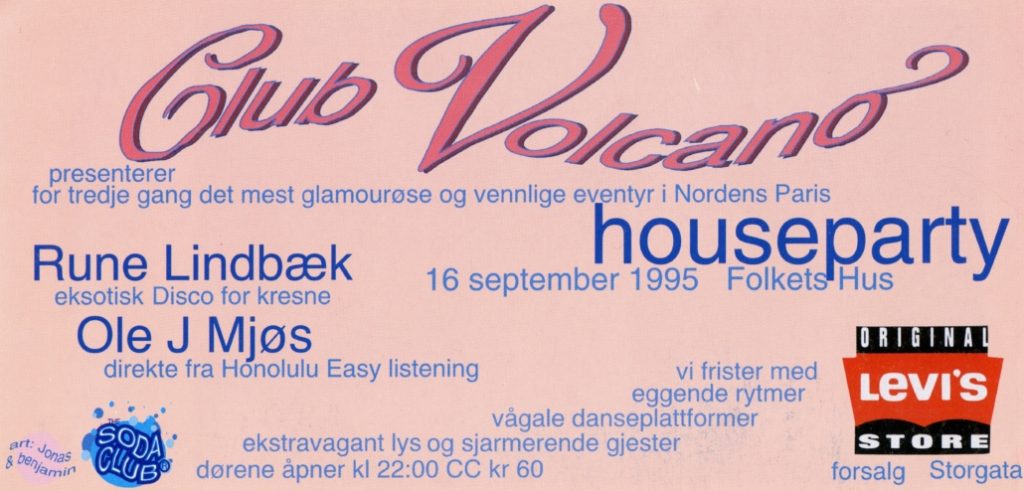

Club Volcano flyer, Tromsø, 1995

How did the Norwegian dance music scene start developing?

The first thing I heard about a synthesiser which I thought was the ‘coolest thing’, but I didn’t know anyone that had it, was that Geir Jenssen’s Biosphere’s brother, who was in my class at school, had several of them at his home. They lived very close by, but I didn’t know him because he was older, but I do remember walking past his house and thinking, ‘he has synthesisers’. Bel Canto went to Ghent to record music and they returned having recorded an album that was really inspired us. Per Martinsen [Mental Overdrive], travelled to London to the first Mutant Waste Company parties which were one of the few places that played ‘Chicago’ dance music. There was a really influential record store in Tromsø called Rocky Plate Bar run by Andy Swatland who was importing music once or twice a week. A lot of DJs in Norway were buying vinyl from that shop because days or weeks after it has been released in America or England you could find it in Rocky. So lots of us were meeting in the import section of Rocky because you could find the latest international music on vinyl; Per Martinsen [Mental Overdrive] worked in that shop, it was very important to us. In the early nineties, I remember Biosphere was in The Face magazine and we were like, wow! We started to get DJs and producers like the Idjut boys and Harvey. People that inspired us were coming here. We were digging their stuff, and they were digging our stuff and that was really exciting, it felt like a recognition of what we were doing musically in Tromsø.

Did you play music on the Radio?

We had Brygga Radio which allowed us to play everything we bought live on the air. It was an independent local radio station it wasn’t a national radio and we would just play Detroit techno at peak times, at breakfast or at drive time in the afternoon because we were selecting the music. There was also Beatservice radio run by an old friend called Vidar Hanssen that I engineered for sometimes. Beatservice used to be on Brygga Radio but moved to the local Student radio. At that time Beatservice was probably more of a synthesiser programme for synthesiser music but it overlapped with Brygga musically, it was fantastic, Beatservice played great music.

Tell us about the Drum Island and Those Norwegians projects?

You could say that Tromsø actually means Drum Island. I like to use real names and word in tracks, and it has some relevance to myself because I’m from Tromsø. I could tell you. The musical project came from my record label also called Drum Island. There was an excellent record label in Ghent, Belgium called R&S Records who we were contacting and Renaat who owned the label loved my Drum Island label name and wanted to get involved, and we thought fair enough, why not! Those Norwegians started because we were listening to a range of music like the early Idjut Boys. UK productions that merged house with disco and we were really influenced by the way they used Jamaican [reggae] dub effects on disco; Those Norwegians made our own version of that. We were called Those Norwegians because there wasn’t any other Norwegians in that scene and it just stuck; I guess we were poking fun at ourselves because the name ‘Those Norwegians’ was actually really ‘uncool’ at the time and we liked that.

Tell us about your record-buying trips to London.

In the early nineties, we would save up money to go and buy records in the UK. Mostly London but also one of my friend’s parents had moved to Manchester, so I used to fly to Manchester and spend all my money at Piccadilly Records, which is still open and a great record shop. I would then fly to London to meet Bjørn [Torske] and return home. I was so skint that my choices were to buy the last Carl Craig 12″ in stock and not eat, just eat soup or not buy it and enjoy my time in the cafes and restaurants of London. I chose to buy the record! Bjørn and I would meet up to go record shopping over a couple of days before returning home together to Norway. We tried to get as many records as we could get from London and Manchester England and bring them home to Tromsø for our radio shows. We also brought back from London cassette recordings of pirate radio shows which were then copied and shared around everyone in Tromsø. If you listen to the first Biosphere album ‘Microgravity’, it’s actually breakbeats from those tapes. Biosphere had a radio show on Sunday nights and this imported music must have clicked with him because if you listen to his radio show you can actually hear elements of ‘Microgravity’. At around the same time parts of Tromsø got satellite television and the daytime sci-fi programmes; all the sounds on this album are sounds I recognise from those shows!

What was Bjørn Torske’s role in the development of Norwegian dance music?

Bjørn was a massive part of the scene, his thing was to fuse his sound with dub and disco. Also, he was very important in the development and growth of the scene because he was among the first of us to move from Tromsø to Bergen. I didn’t really feel the Bergen Wave, it was more a case of just Bjørn and old friend Erot who were making music. The ‘Bergen Wave’ name was just a typical UK way of reporting and making linking it to a specific geographical area. It wasn’t like Bergen this and Oslo this, Bjorn was from here, Tore [Erot] and Annie were from here and staying at mine. Tore & I used to hang out when I used to live in Oslo, as a producer and inspiration he was very important for Norwegians. His productions have a bit of quirkiness in them and they still work on the [dance] floor when I use them as a DJ.

What makes the clubbing experience so special?

When I DJed in Oslo, Skansen was a fantastic, very hedonistic club, along with other great places in Oslo like with Jazid, Head-On and Blå. It had a great sound system for a converted public toilet that had been closed for ages. It was tiny and we didn’t need many people to create an atmosphere, and it had tonnes of atmosphere! The best clubs in Norway though have probably been in Oslo, it’s the smaller sized clubs that get ‘packed out’ as you don’t need many people or really pumping [hard] music to get the dancefloor going. You just need a few heads and a great atmosphere, and there are plenty of ‘weirdos’ who like to dance in Oslo! The clubs have definitely been a factor in shaping the music we make as you don’t need to reach thousands of people in the club. If your music reaches the right people, the experience inspires you. If this were a place where you needed mass appeal, big [superclubs] clubs with hard sounds then our music would definitely have sounded different. This was a smaller version of Berlin with little basements or jazz clubs, not made for a lot of people, but for the right people. The nights at the legendary Nomaden in Oslo were also very important to try out new music on the crowd. It’s one of the few places in the world where you could play this [specific] kind of music and the dancefloor would scream, it’s one of the best clubs that has ever existed.

Those Norwegians – Kaminsky Park album artwork, 1997

Why do you think Norwegian music is influenced by such a wide range of music?

I think the collective influences from the people here are one of the main reasons, a lot of people who produce electronic dance music in Norway have large record collections. There are synthesiser guys, dub guys, Kraut guys and disco that came before us and now we can just make our own ‘local’ version of it with a ‘Norwegian twist’ because we have the technology, they didn’t. We gained confidence from our record releases which did ok amongst the people we consider it important to reach. This bred confidence between us. Norwegians were producing some great records; you’d play them out and they worked on the radio and in clubs and the locals really liked it. They didn’t realise that it was Norwegian music. Some of the biggest records I’ve played in my 30 years of DJing have been made in Norway.

Could you tell us about Frode Holm’s role in the Norwegian scene?

There didn’t appear to be many attempts at making disco in Norway and we had all been trying to find traces of proper disco [being produced in Norway], then we found Frode Holm who was running a record shop in our main hangout in Oslo. His best track ‘Fotspor’ from his 1981 album ‘Holme CPU’ has fantastic production, great vocals and lyrics which tell a story about going out into the world and marking your mark. There might not be much going on in your local area, so you can go to LA, New York or San Francisco in North America. I can relate to these lyrics because in Tromsø until we started doing parties, I really wanted to be somewhere else. I can really relate to the feeling that you don’t want to be stuck in the same place forever. Probably why I ended up in Oslo of course, it’s such a fantastic city. Frode’s music was influenced by really pure disco, jazz-funk and soul but with a Norwegian lyric which made for an odd record that was so important in Norwegian musical history. So Frode was a pioneer here in Oslo, of a generation born twenty years before us but doing what we are doing now, back then.

When did you start DJing internationally?

My first gig abroad was in North Yorkshire, in 1993, when I was studying journalism at Darlington College in the North East of England. There was a record shop in Darlington where I met Moonboots who was putting out twelve inches. I had heard a rumour about this record shop in a derelict area of town behind some garages, as I walked past, I heard a bass drum and went through a door. I thought I’d arrived in heaven. It was packed with people, shrink-wrapped American imports, even back then! From 1998 I was a bi-monthly resident at Plastic People in London. I started going to London on the last British Airways plane on a Saturday afternoon and flew back on the first plane Sunday morning. After that, we discovered ‘Sunday Best’ which was a key club event in the timeline of disco and Balearic music, and it became a home from home for me. Around 2000, I started DJing in Easter Europe more and you think that Eastern Europe, just after the Berlin Wall came down that it would be dull and grey. Wow, they like to party. I have DJed at so many gigs and they’ve been fantastic. My style of DJing is not for every club, so the number of places I can play is limited but I DJ once a month somewhere in Europe and have a great time. I perform in clubs that want to hear good music, I put in ethnic elements, dub it up and have a bit of fun, try not to be so serious. Dance music resides in a strange world but I’m really happy to be a part of it.

These excerpts were recorded and transcribed, with some parts of the interview used in the final print of the Northern Disco Lights feature documentary film.

© Paper Vision Films t/a We Are Woodville Ltd 2016

Recorded on a Zoom H2.

Transcribed by Fingertips, Louie Callegari and Tongue Tied.