We’ve got a bit of a different take to our ‘Out The Box‘ feature this month as we welcome the self-professed ‘DJ, Painter & Musical Arranger’ Justin Robertson. A long standing friend, comrade and consistent peer for us here at Paper. An effortlessly amazing DJ and all round creative soul whose recent debut novel ‘The Tangle‘ has been described as a trans-dimensional trip into the mysterious knot of nature, a journey into the ‘brilliant darkness’ where the timeless divine spirit of the ‘Tangle’ weaves its spell”.

We asked him to be part of ‘Out The Box’, of which he has delivered a mini-novella about his time spent in Kensal Green cemetery and the many notable souls that reside there. Gothic & beautiful in equal measures.

Once the strobe light has ceased its incessant chatter and the dry ice has been sucked back into the lungs of the great rave God, I like to spend my time with an entirely different crowd of people. The dead. They are no less enthusiastic. Some are definitely up for in depth conversation or an intriguing tune, it’s just the medium of delivery that’s different. It’s more of a psychic link into the underworld, a silent connection, a posthumous mind meld. Rest assured here in Kensal Green cemetery there is a constant cultural carnival going on beneath the London clay and behind the walls of the carved stone tombs. I have made a lot of good friends there.

Kensal Green Cemetery, photo by Nicholas Ball

Just inside the gates that open up to the crematorium, the hum of the Harrow Road blends into the chatter of bird song and the creaking of old trees whose roots drink deep from the charnel well. Foxes, mice, rats, and the dead. This is their village. The rest of us are just tourists. The most curious residents are the flocks of bright green paraquets who have made the graveyard their home. Liberated from the cruel cages of pensioners they have formed a colony that brightens the grey branches and gives the cemetery an almost tropical feel. Close your eyes and you could be in a Brazilian rain forest.

The dead have no need for asphalt. Though there are one or two paved roadways that carry the hearses and mourners’ limos the most interesting routes are down the muddy rutted paths. This is where the dead live. Some of my best friends reside alongside these claggy tracks. Willkie Collins the author of the Woman in White is usually one of my first ports of call. The novel was his fifth book and definitely my favourite, a tale of patriarchal skulduggery in 1850’s Britain, a classic by anyone’s standards. If I’m stuck on a plot line then Willkie is more than happy to lend a hand from his modest stone mausoleum. Just across from Willkie Collins, passed the tomb of Charles Blondin the famous tightrope walker you come to the magnificent porticos at the rear of the central chapel, the setting for several films and photo shoots of a gothic and horrific persuasion. Last month I watched a crew filming what appeared to be karate vampire hunters dispatching a horde of the undead on the steps of the chapel. They were later spotted, still in full make up, enjoying a ploughman’s lunch at the nearby Mason’s Arms, a pub which is itself often the scene of many horrific nights of self-abuse and acid house zombie raising. The supernatural arts are exalted in NW10.

Mason Arms, Kensal Green

In the shade of a venerable old tree to the left of the chapel entrance is the simple but massive grave of William John Cavendish Bentinck Scott Fifth Duke of Portland, an eccentric noble who put down roots in the cemetery in 1879. Celebrated in fiction in Mick Jackson’s wonderful 1997 novel ‘The Underground Man’, also known as the mole Duke, he spent the family fortune constructing a vast network of underground passages under his estate at Welbeck Abbey, large enough to accommodate a horse and carriage he took to riding to and fro under the estate grounds in the middle of the night. He also trepanned himself for good measure. I make sure to say hello when I’m passing though he seldom gives me the time of day.

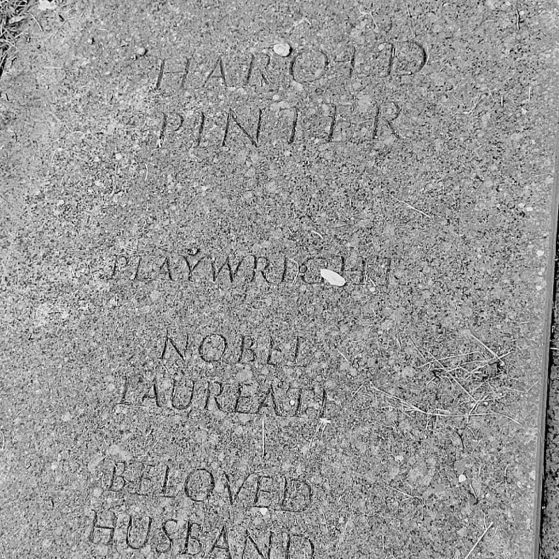

Harold Pinter, Photo courtesy of Justin Robertson

Down the central boulevard where some of the most splendid tombs are located you can call on a variety of ex Imperial scoundrels and capitalist exploiters whose names are largely forgotten despite the grandeur of their homes. I tend to give them a polite but cursory nod as I seek out more nourishing company. Two of my favourites for challenging conversation and literary inspiration live just off the central avenue. Firstly, the grave of J.G Ballard foremost writer of the late 20th century. The poet of the suburbs. The grand duke of dystopia. The man who gave voice to the horror behind the twitching curtains. The author who made the concrete, steel, and exhaust fumes of post-industrial Britain shimmer with menace. The author I’d most like to be. Harold Pinter lives next door give or take a tomb or two. The master of the pause… The dramatist who conjured the comedy of menace from the gaps. We often laugh about how absurd it all is.

Count Suckle by Marcus Painter

Further down the road is the grave of Ras Andargachew Messai of Ethiopia son in law of Emperor Haile Selassie right next to the grave of my next-door neighbour’s dad. Get to the fork in the path and hang a right you’ll find William Makepeace Thackery author of Vanity Fair. His grave could do with a good scrub if I’m honest. He often complains about it. Carry on down that same path which runs parallel to the canal, and you will hear the sound of good times vibrating through the soil. Even in the silence you can feel it. Even in death the sound will never die. On a modest mound lies Count Suckle UK reggae sound system pioneer. Next to him Count P, who ran a Kensal Rise based system and was one of the first soundmen of Asian descent. This corner of the yard contains some of the cemetery’s most lively characters. I’m always sure of a warm welcome as I wander by.

Take to your wings and fly above the graves, look for the anke cross on a black tombstone. You have found the simple but stylish resting place of Ossie Clark couturier to the stars and decadent prince of the King’s Road in the swinging sixties and flamboyant dystopia of the 70s. He always advises me to loosen my look up a bit, though he generally approves of my berets. On the way back home, I bow to the genius of Ian Loveday, electronic pioneer and the producer known as Eon, resting next to his pianist mother Ruth. His grave is shaped like a marble record. It’s kind of beautiful. I can hear him making machines sing as I leave the morbid housing estate, waving at my friends as I go. Adieu. But they are not really there. They are everywhere.

The graves are just symbols. Random markers where flesh turns to bone and life is reborn from the rot. The dead never die. I know because I’ve met the dead. Some are truly lovely. Some of them are assholes. As in life so in death. But death is just a change of state from something you can meet down the pub into something that you can meet anywhere. The dead are everywhere all at once. Pub, hearth, heart. You are never lonely with the dead, everyone I have ever known and loved is still here. Some people I had never met in the flesh are now my best friends. We meet regularly in this magical spot. Kensal Green cemetery. Just another address. A spot on a map. But under the earth and in the air the dead are having a blast. It can get pretty crowded in the saloon bar of the hereafter but unlike most nightclubs you don’t have to shout to get served.

Justin’s website is HERE

Support his writing: The Tangle by Justin Robertson