Memoirs from Norway’s underground dance pioneers: Per Martinsen #1

Travelling around Norway in the Spring is a fantastic experience. During my trip in 2013, we hooked up with the key movers and shakers involved in forming the country’s house and disco scenes. I was lucky enough to touch down in Oslo, Bergen and Tromsø, and many weird and beautiful places in the surrounding areas. I travelled with Ben Davis, who was directing the film we were working on, formed from interviews with the key people from the dance scene plus Paper Recording’s label artists such as Those Norwegians. We were also curious about the country, geography, and people and how they influenced each other’s creative passions. This film had a working title of ‘Northern Disco Lights – The Rise and Rise of Norwegian House Music’. During our visit, we spoke to as many of the DJs, producers, promoters and radio stations as we could and decided to publish these best bits that sum up the trip, the film and our findings.

Per Martinsen is a sonic artist, electronic music producer [Mental Overdrive], DJ and performer from Tromsø, Norway; he’s also one half of Frost with his partner Aggie Peterson.

Hi Per, tell us what it was like growing up in Tromsø. Tromsø geographically is on the outside. It’s the biggest town this far north if you look down the planet from the top. A lot of cultures are based around the survival needs of living here, so when we grew up this shaped our culture, we were told: “This is where we’re from and this is what we do”. When technology-based means of communication and creativity such as the internet came into our lives they were organically integrated into our culture. I grew up in the 1970s and moved away in my late teens, before the internet and even before Norway began fully using the English language so communication with the world was difficult but growing up here was perfect because we could just sit up here and monitor the world. We could sit here and watch what the humans were up to in other parts of the world. We ordered fanzines and music from the UK and Europe and the UK and we had little import sharing ‘factories’ where one of us would order a record, we’d copy it onto cassette and distribute it around Tromsø. We imported a lot of youth cultures such as post-punk, early German electronic experimental music, Freaks from the West Coast of the US and even bands like The Residents performed in Tromsø in the nineteen-eighties. Here we were, sitting on top of the world looking out, trying to find things we thought interesting going on down there, where the other people were. We collected everything in to a big heap that we shared amongst ourselves. We would import mail order records, fanzines and cassette tapes and copy the music onto tape to share and lend each other the literature to read.

Did you all go to the same school or college in Tromsø back in the day?

Some of us lived across the bridge, on the mainland in Tromsdalen (Geir, Bjørn, Rune, myself), but due to age difference, I only knew Geir from outside school and didn’t meet the others until after finishing school. Kolbjørn, Aggie and the Royksopp boys grew up on the Tromsø island and went to a different school.

Was there Norwegian culture that interested you or was it all from abroad? Most of it was from abroad and ultimately Norwegian dance culture started emerging, but when you are situated in Tromsø you are three to four hours’ drive from the nearest town, 2,000km from Oslo. It’s all viewed as just the ‘other place’, there was a lot of relevant parties and people in Oslo and other towns that I didn’t know anything about until over twenty years later. It was more difficult to get information from around Norway than it was to find out what was going on in Berlin and London!

Do you think Tromsø’s isolated geographical isolation influenced the music that you began to make? I think when I grew up here eclectic was the best way of describing the music production we made because we didn’t know what was right or wrong [there were no parameters]. The first time I met somebody who was into ‘drum & bass’ and not ‘jungle’, I was like “Oh, wow you do exist”! People are perhaps more fragmented in larger cultures because you have to choose your ‘place’ or ‘position’ in that scene or culture, but when we grew up we had total freedom because we could just sample everything, put it into one big cauldron and start mashing it up. I heard music through teenagers when I was pretty small and the radio [National radio] didn’t play any exciting or cutting edge music but there was one programme I listened to on NRK P1 with Harald Are Lund, he played interesting music. The British music papers were very much in demand up here as we tried to follow what was going on in the underground music scenes around the world. The crowd I grew up with really wanted to explore different soundscapes and scenes and were very curious about all forms of alternative music. There was a guy called Jon Strøm (who was a couple of years older than me) who used to invite people like me and Geir Jenssen around his house on Fridays to drink beer and listen to the mail-order ‘catch’ of the week. It would be a very eclectic mix of punk, post-punk and pop and he would introduce us to records by Crass, Dead Kennedys along with ABC and Chic. I remember hearing “Last Night a DJ Saved My Life” by Indeep and “Warm Leatherette” by The Normal for the first time at Jon Strøm’s. He ordered some of his records from Rhythm Records on Portobello Rd in London but not 100% sure. We ended up having eclectic influences such as electronic, punk, pop or experimental music, the music just had to have something special.

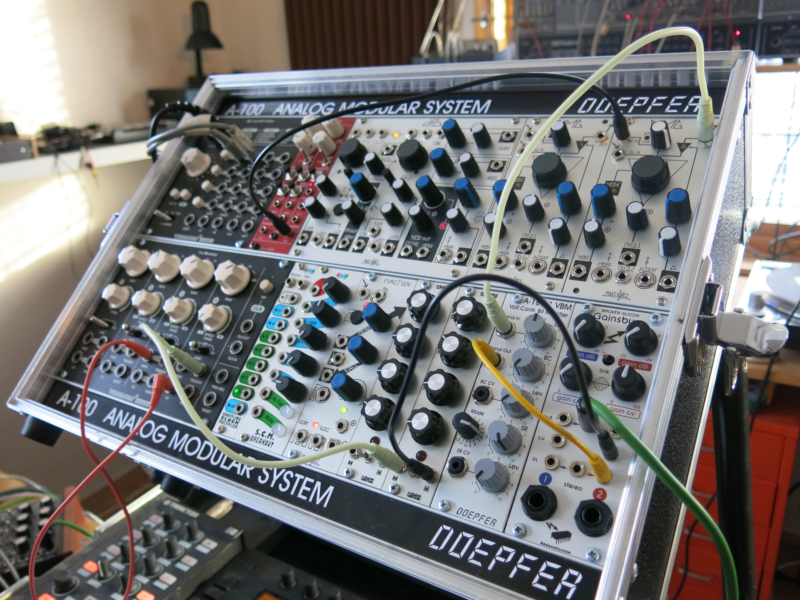

Doepfer A-120 Analogue Modular Synth in Per’s Studio

Tromsø and Norwegian electronic music seem to have this otherworldliness. Do you think it reflects Norwegian identity? It’s a strange question for me to answer because if the music we make has something special like a local flavour or oddness then it’s a question that should be asked of someone outside of Tromsø or Norway. It’s hard to analyse your own or my [connected] contemporaries’ music. You do what you do, and you put it out there and see what reflects other people’s opinions. I don’t need to be shaped by what surrounds me and that is the freedom you get growing up in Tromsø, we could sit here and sample every kind of alternative or strange music from any global subculture and spit back our version; we didn’t have to fit in anywhere. If I grew up in a bigger city where there was a [specific] sound I would [potentially] start trying to fit into that [city’s] ‘sound’ and the creative freedom of not having to respond to your surroundings is great. Dance music is such social music, it is a language and you can communicate something with it. It needs to work on some level but as long as it makes you move, or appeals to you at a basic level then you can put as much of yourself into it as you want; that is the freedom that comes from the Tromsø scene. You don’t answer to anyone. You just make what you want to make.

Tell us about Geir Jenssen’s role in the Tromsø music community. Geir and I met when I was 11 years old and he was three or four years older than me. We shared a love of the great outdoors and met in a mountain cabin and it was the first time I’d heard Kraftwerk’s ‘Man Machine’ on a portable cassette deck. Geir was a dedicated music fan who got the best stuff and really followed what was happening, and he told me one day, “I’m going to buy a synthesiser and start making music”. We already played in bands, but he started making electronic music and it was brilliant. I don’t remember the year, but it was when bands started the transition from rock into electronic bands; I already owned drum machines and we started to play around with them, and managed to get hold of some synths: Korgs, MS10s, MS20s, begged and borrowed until we got what we needed and then we started making tapes. I even used a cassette deck as a sampler using rewind techniques. We had a great time experimenting (and struggling) to make our own sound.

Northern Disco Lights 2017 screening at TIFF (Tromsø International Film Festival)

How important was his success with Bel Canto on your developing career and scene? We were all making music and performing together but they went off to Belgium, and I went to the UK around the same time. We always met up when we returned to Norway to share experiences and play each other’s music. Many of us [Tromsø artists] started releasing records around 1987-88 and the fact that they were released on international labels gave us all confidence. if you look at the punk scene in Tromsø there are only two or three single releases, but if you look at the punk scene in Oslo in the late 1970s or even Trondheim, there’s tens or hundreds of bands releasing singles. We were up in the Arctic and just to get somebody to transport a pressing of 500 seven inch vinyl up to Tromsø would be very expensive and could ruin you. Also, when they arrived, they would just sit in your basement and it was really hard to get them back out into the world because we were so far away [geographically] in Tromsø.

How did you start producing music and was it just for yourself and friends? I started making noise when I was a kid. I was banging and drumming on anything, I would find and destroy my mother’s cookie jars. I just needed [to release my] energy and make [turn] it into sound. We started bands when I was about 13-14 years old. Punk had just happened, but I liked the aesthetics and the DIY ethic of the punk movement rather than the music. I didn’t really enjoy the music but after in the post-punk era was a brilliant time to kind of be interested in music. Those were the formative years and shaping of my musical tastes. All the bands I was listening to started using drum machines and I tried to play like a drum machine. Bands that influenced us were mainly UK based such as Joy Division and then New Order and they began getting influenced by American dance music. I had this record from a Canadian duo, I didn’t enjoy the music very much, but they looked like New Romantics sitting at a coffee table and on this table was this ‘crazy’ machine. I was like, “What the fuck is that machine?” as it just looked awesome. I went to the local music shop and took the album to ask what it was? and they said, “a Roland”. This was maybe in ‘83 or ’82 and they telephoned Roland, and it was a TR808 drum machine. I was like I want one of those. I realised that this was the same machine being used by Arthur Baker productions and a lot of the records I was listening to. I worked for the whole summer in between school and spent all my money on a TR808. That was my first machine. It was perfect and it did the trick. I don’t have it anymore, but I still use its sounds. We were really opposed to everything around us and we tried really hard, perhaps too hard to create our own little space. We were trying to do something different but at the same time absorbing lots of brilliant influences coming from elsewhere. We tried to copy interesting music and when we were successful at the copying it turned out a bit boring but when we were unsuccessful it turned out very interesting.

What did your parent’s generation think of this? The established traditional musicians and crowds in Tromsø already hated the punk scene when suddenly these people came on stage to perform without traditional instruments they were outraged. The only way to be a rebel was to do something that had never been done in Tromsø before. Mine and Geir and I guess Runes parents were working class, but I believe Bjørn’s parents were academics connected to the University. I don’t think any of us came from families involved in creative, art, performance industries.

When & why did you go to England? I actually left Tromsø for Oslo in the mid-1980s but I didn’t find much going on, so I returned to Tromsø and worked in a record shop and then travelled to the UK by chance really. I just got on a train and ended up in Copenhagen, met a friend and we moved around Europe together until ending in London. Luckily, I met some people who were squatting in Hackney and suddenly I had a room for a few months. After that, I had an opportunity to work in a recording studio in Brixton called Cold Storage Studios where a few of the bands that I listened to were based.

What was the London dance music scene like when you were in the UK? The first Detroit Techno and Chicago House cassette tapes started circulating just before Christmas in 1987 in Hackney and during the winter of ’88 I really got into it. I was already into electronically produced music but when I heard ‘Detroit Techno’ for the first time I immediately understood that need to be investigated! One of my friends came over to London in the early summer of ’88 and was really eager to hear what was going on and I was willing to share all of my new music. I remember returning to Norway for Christmas that year and meeting up with Nils Johansen from Bel Canto as he was on Christmas holiday from Belgium. He asked me what kind of music I was working on and I explained there was a lot of techno and house music in London and he said: “What’s that?”. I didn’t have any music with me but he had a synth rig set up in his room, so we went back and I played him some of the sounds and beats and a few months later in London I had a phone call in the studio from Mark Hollander who owned Belgium’s Crammed Discs label and they had started a new dance subsidiary called SSR. He said, “I really like the demos that you made that Nils played me. Can you come over to Belgium and finish them?” I was really surprised as they were just demos but, of course, I went to Belgium to work on the tracks.

Can you remember the first time Bjørn and Rune came over to see you in London? I took Bjørn [Torske] and Rune [Lindbæk] record shopping in Soho and they were so excited, we had a real laugh. I think Bjørn was the most enthusiastic person I had ever met in my life. He was so genuine about his interest in music that it was really fascinating. It was like wow!

When did you return to Tromsø from Belgium? I went back regularly to see my family as I have two younger brothers who were teenagers at that time, and I had lots of friends there still. We had some parties and I got to know Bjørn Torske and other people younger than me such a Kolbjørn Lyslo who had been buying records off me in the record store a few years earlier. There were a lot of young people making brilliant music.

Bjørn Torske & Per Martinsen in the Yorkshire 2016

Where do you think they found their creativity and inspiration? They were probably just geeks into synthesisers and electronic music because already when I was at the record shop [Rocky Plate bar from ’85-’86] there were always people creeping out of the woodwork asking for weird, challenging music that I didn’t know anyone but myself had heard of. They probably got their hands on information and music culture the same way as me before the internet took over the job of providing information.

Can you tell us about the first parties you put on in Tromsø? The first club playing house music was when Bjørn & I decided to put on a rave. It was very DIY. We combined our record collections, made all the décor and rented a sound system. I was into hobby electronics since I was a kid and managed to build two strobes and then we were given permission to hold it at the Brygga Ungdommens Hus (Youth Centre). We designed and photocopied flyers and everything was set, it looked fantastic and we had our rave, me and Bjørn. He was playing, I was dancing and then he went on the decks and I went on the decks and he danced. That was the first house club in Tromsø, Norway. The classic two-man party. After that, I was asked to DJ at a mainstream disco in Tromsø a Saturday night. There were a lot of US marines based here from Chicago and I think they were quite used to house music by 1988. The club was packed and completely ‘going off’, kind of weird. All these people were asking me, “Where the hell did you get this music?”, “How can this be? We’re in the Arctic” and “How can this happen?”. We had our moments where we were successful in bringing these sounds to the locals here as well; not just exporting them.

Was there a moment where you would say there’s a Tromsø scene? There was definitely a ‘bedroom movement’ going on because when I returned home one time, a handful of the younger producers came to our studio to produce their recordings. Some of these sessions were sent to SSR in Belgium and released as the two T.O.S. [#1 & #2] EPs and these were the first releases by Bjørn Torske, Ole Johan Mjøs and Per Syamese.

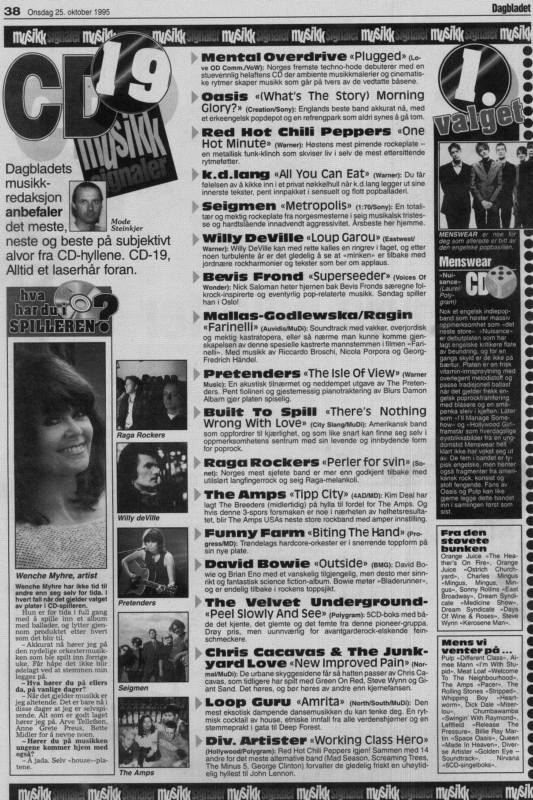

Per Martinsen’s Mental Overdrive smash the national charts in Oct 1995

Can you remember what happened around the emergence of Tellé Records in Bergen? Bjørn ended up moving to Bergen after we had played at a party there and I would visit all the time to this great club called Café Opera. It was at Café Opera that he introduced me to this really young guy. I had my portable DAT player (a very important piece of kit then) and this guy (who introduced himself as Tore) gave me a DAT, I listened to this amazing music. That was Erot, Tore’s first productions. Once we had both heard it, we immediately knew that this music had to be heard and we ended up releasing two of the tracks. The label was called Footnotes, Tore did the artwork and the tracks were called Milk Chocolate Swing and Haribo. Footnotes only had one release which was Tore’s first production. That was my first experience of the emerging Bergen scene, which blew up in the international media with the help of Mikal’s Tellé Records that released all these amazing 7″ singles with brilliant music. The main element of the Bergen sound of the ‘90 was pop. It was brilliantly crafted alternative pop music. It was very eclectic with different producers such as Erlend (Ralph Myerz) and the Kings of Convenience that had a Simon and Garfunkel sound, it was very creative and artistic. These original energies come and a scene explodes and everybody is inspired and then it dies out and something else comes along and takes over but it was an amazing couple of years. The two main musical exports from Norway have been Black Metal and electronic music which reflect a certain level of international success when Norwegians look at themselves in the mirror, and this inspires others. There were so many female electronic pop artists from Norway, it was amazing; we’re such a small population but have a lot of people working in the music industry.

When did you first become aware of Röyksopp? I was playing at the festival here in the 90s and when I was setting up my gear four young lads came up and said, “Hi, we’re playing the support slot for you,” and they called themselves Aedena Cycle. That was Torbjørn [Brundtland] and Svein [Berge] from Röyksopp plus Gaute Barlindhaug and Kolbjørn Lyslo. That was their band and that’s maybe the first time that I met these guys, they were younger than Bjørn’s generation and they were the next generation of youngsters breaking on to the music-making scene. Tromsø had all these young, very enthusiastic people and it was really refreshing meeting them all. All the time there were ‘new faces’ that turned up with new music for me to listen to, and they were always driven by this mad energy. I loved it. You really want to listen to music made by people like that. Most people say, “Listen to this,” and you’ll probably listen to it eventually but if they are right in your face and the sun was coming out in the middle of the dark season you know it’s going to be refreshing. That was my first, very positive impression of Röyksopp. Torbjørn [Brundtland] moved to Oslo to work with Bel Canto on one of their later studio albums. They were in the next-door studio, so we spent some time together listening to each other’s music. Then he started playing me a lot of his own music and it was fantastic; really, good. This was pre-Röyksopp and there was probably some of the tracks that were released on the Those Norwegians album [on Paper Recordings], but it was via Torbjørn’s cassette and DAT, tapes that I heard what was going on with that crowd.

Has dance music changed your life? Yes, in a big way because I hated disco when I was growing up, I hated dancing. I had decided that I was never going to dance in my life but then, I heard quality dance music and some proper disco not just the pop charts stuff, so yeah it changed me a lot. It’s had a massive impact on my life. I think electronic producers in Norway have brought their own character to the sound. Every city or locality will have its own sound or technique that is inspiring to others, this new disco [Nu-Disco] production style established itself globally but I would love to see more challenging productions because I need more edge, more noise. I’m just an angry old man!

Insomnia Festival 2003 – Frost and Per Martinsen

How important is the Norwegian identity to your music? It’s strange because these days I probably have more in common with you than with my next-door neighbour because we’ve been interested in the same kind of culture and music. On one level the common references are closer than somebody you share a country with. On the other hand, you can’t go anywhere in the world and not bring ‘yourself’ with you. I’m always going to be Norwegian. I’m always going to be Northern Norwegian because I’m very connected to this landscape, and I really like rubbish weather. If it’s too hot I stop functioning and I have all these things built into my genes growing up here; I’m shaped by the people and environment here, it’s important that I’m Norwegian.

When did that turn into something that you thought good enough to release and share with the world? The first was a cassette release in 1984. It was Geir’s project under the artist name of E-Man and released on a cassette label based in Oslo called Likvidér; I worked with him on a couple of tracks that ended up on that tape. Geir released quite a few tapes at the time as he had invested in duplicating machines so that he could copy cassette tapes, photocopy the artwork and sell them via his mail-order [Biophon]. There were two punk bands in Tromsø that released seven inches but the cost of vinyl manufacture and distribution from so far north in Tromsø was prohibitive, so people saw cassettes as an opportunity to get their music out there. There was a lot of brilliant cassette releases from local bands in the 1980s that never saw the light of day.

Per Martinsen’s Mental Overdrive smash the national charts in Oct 1995

How did you get swept up in the acid house movement? I ended up in London, England in 1987. Ever curious and a big fan of ‘industrial’ electronic music, a lot of these bands performed live in London so I just ended up just going there for gigs and hang out; I ended up living in a Hackney squat for most of ’87 and ’88. I hadn’t consciously set out to end up in this situation, but I was lucky because everything that was happening then in London during that period was so exciting. I remember the first time I heard Chicago Acid and Detroit Techno music on a cassette tape given to me by a guy who was also squatting nearby in Hackney. He was called Mark Van den Berg, [Mark Luvdup] and that first tape was shared around everybody; we then started going to parties and warehouse clubs. I was ecstatic when I heard this music for the first time because in Tromsø the reaction to my productions was generally “Yes. Love the drum machine and bass lines and stuff but where’s the song?” I didn’t want them to be songs. I wondered whether there was a place for this music in the world, was it just for myself only? But, on hearing electronic dance music a couple of years later that was just ‘instrumentals/dubs’, and it was a revelation. It was like okay there is a space for this kind of music in the world and it’s in the clubs. Geir was with me in the UK at that time and we ended up working as tape-op assistants in a Brixton based studio, and since I had some of the gear that they needed in the studio we did kind of a swap, giving me access to the studio at night time, I’d help out during the day and sleep under the manager’s desk on the floor when needed!

What was your first commercial release? My first release was on the Belgian label SSR. The track was produced by Geir & me and was called ‘In Your System’. When I was working in the UK, Geir and his band Bel Canto frequently travelled to Belgium to record and release music on Crammed Discs. I went home to Tromsø at Christmas 1987 and I explained about this new house and techno music to a good friend of mine, Nils Johansen who played in Bel Canto. I struggled to explain so I said, “Okay switch on your rig and I’ll show you,” and made some quick examples of the music I was currently working on right there and then. Nils played these demos to the Crammed Discs label owner Mark Hollander who invited me to Belgium to finish the tracks. The tracks were released on a new dance music subsidiary they were setting up called SSR (short for ‘Sampler & Sans Reproche’) and then later on R&S records. Geir started working on his Bleep album just before Biosphere in Belgium and I did a project with Samy Birnbach, [DJ Morpheus] who created the great Freezone compilation series for SSR/Crammed Discs. We did a track called ‘Hallucination Generation’ as the Gruesome Twosome that totally blew up in the US and they wanted us to follow it up but I had already moved on and started returning to Tromsø to work on new projects.

When you returned to Tromsø how were Bjørn and Rune begin fitting in with the community. I’m a bit older than them and there was a bunch of eager guys hanging around my younger brother who was six years younger than me but the same age as Bjørn and Rune who knew him. When I came back with all this new music which was emanating from our house, they got really into it. They began borrowing records, especially Bjørn for his radio show on Brygga. We produced some tracks together for Mark Hollander after Geir [Jenssen] had played some of the demo music they’d produced to him. Bjørn, and I think Rune Lindbæk or Ole Johan Mjøs ended up releasing the ‘TOS EP’ No. 1 and No. 2 ‘TOS – The Remixes’. TOS was the airport code for Tromsø.

Were you aware of any other producers or electronic music scenes in the rest of Norway? I didn’t know of anybody outside Tromsø that was into this kind of music in Norway. I had heard that there had been a club going for a couple of years in the small town of Lillestrøm outside of Oslo but that was a couple of years later.

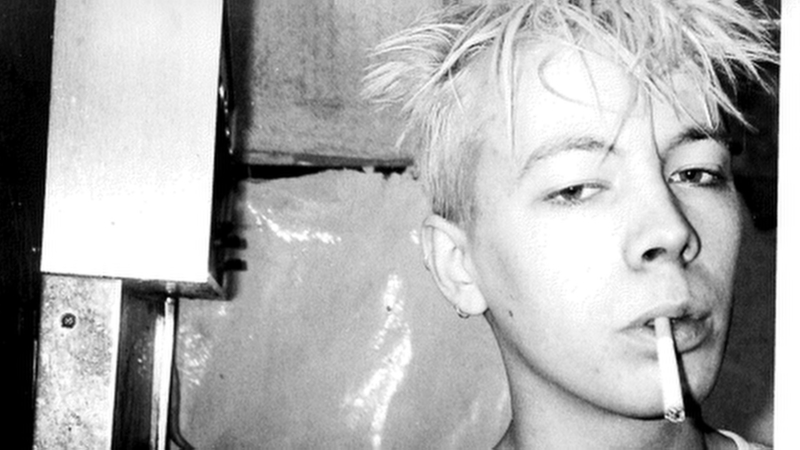

Mental Overdrive_London, circa 1992

Why do you think Tromsø was such a fertile location for making music? Tromsø is great for taking the time to get immersed in your projects, and in the dark season what else is there to do? You sit inside and you make or listen to music. It’s a great place to contemplate and be productive. You don’t run around town to parties and gigs all the time. Although there was a very vibrant music scene with gigs every three months. Pretty strange music was classed as amazing and bands like the Residents were huge in Tromsø. They were even bigger than Aha!

When did you first kind of become aware of an Oslo music scene? I ended up moving to Oslo in the early nineties and by chance, was invited to DJ at a party thrown by DJ Geronimo from Lillestrøm. They had been running a club for a couple of years in Lillestrøm (a small town outside Oslo). I made new friends from that crowd and started playing the odd DJ slot at their parties. It was a long journey [from Tromsø] but I was like “how much time do I have on this earth?”. In Oslo during the early ’90s, as in every European city, we arranged some of the first legal raves and had guests like Aphex Twin, CJ Bolland and Outlander. I did support slots for bands like The Prodigy in huge arenas, but [I realised] this was not the reason I got into music. I decided to leave the techno arena rave circuit and return to playing the music we liked in small bars. That’s when I met Pål Strangefruit who had just moved into town and he was my favourite DJ at the time. The scene kept going with clubs like Jazid and Skansen for a few years and that’s when the Oslo style of disco was born. Dan & Conrad, Idjut Boys came over to DJ frequently as they were our favourite DJs at the time. Local music was being produced and I made some tracks with an English producer called Nicholas Sillitoe under the name Illumination. We did a few singles, then an album and suddenly we had a creative, vibrant club scene with lovely music and people, everything you need to have a good scene.

Why do you think Norwegian electronic music has such a strong connection with disco? The mid to late 90s club scene of Oslo and Bergen brought disco to the attention of Norwegian clubbers. I grew up hating disco. It was the worst thing ever but I couldn’t understand why I felt like this? I worked out there were two reasons. The first was that growing up I was never played tracks by Patrick Cowley or Arthur Russell Productions; I was just played chart music. The second reason was at the school dance when I was 11. They were playing some amazing disco tracks, I got carried away with the groove and started dancing with some girls and I was in heaven! Getting down to the groove and that was my acceptance of disco music! But the school bully was stood next to me and while dancing, I knocked his fresh new bottle of Coke right out of his hand. At the time, a bottle of Coke cost as much as a skyscraper and he really threatened me; I think that was the moment when the word disco left my vocabulary. and I stopped listening to it. Now, listening to disco is like therapy for me. I also had conversations with Renaat from R&S Records in the early 90s when I was really into hard techno, he loved disco and tried to convince me that all dance is rooted in disco and that I was living in denial! Later, Bjørn [Torske] started bringing along all this great disco and when Tore (Erot) started producing I realised that my personal relationship with disco had been one of trying to come to terms with it, obviously now I understand it’s part of the foundation for all the music I love. The most influential years were when Hans-Peter Lindstrøm and later Todd Terje emerged onto a very health Oslo scene where small clubs were playing great music laced with disco. I rediscovered this great disco music from the past that I had missed out on.

Kvaløya (Whale Island, Tromsø), 2013

Can you talk about Tore and his role in Norwegian music? Tore was serious when it came down to making his disco music. He came to my studio with a keyboard and played his own solos which were then used in my sampler to put them into tracks; he was so focussed with nothing left to chance. Tore was a very funny, lovable and kind person.

You, Bjørn and Röyksopp and a lot of Norwegian producers have a real sense of mischief, why? I think you should take your music seriously but not yourself and if you do your friends will tell you. This is a good way of keeping people on their toes and I think life is like that. If you don’t make your own fun you’re not going to have any.

Can you tell me about when you and Bjørn delivered the album to Joakim at Smalltown Supersound? He released some of my music on Smalltown Supersound and he began talking about Bjørn all the time, asking me “What’s Bjørn up to and will he release anything?” and he really wanted to put out some of Bjørn’s music. They started talking and agreed on doing an album and eventually, Bjørn put the finished album onto a CD master. He called me and said, “How are we going to give this to Joakim?”. We decide on a fun way to do it. I took my camcorder and Bjørn’s CD master to Oslo airport filming myself arriving on the express train, walking through the station to the luggage lockers. I held up the CD master and filmed the number of the box and put it in, turned the key and stopped filming. I then went to the local post office where Joakim had his PO Box and I put the luggage locker key in an envelope and wrote Joakim’s name on it. Since it was also my post office, I started chatting to one of the guys working there and I said, “Can I just put this in Joakim’s PO box? It’s just right there.” And he was like, “It’s not how we usually do it but OK this time”. I managed to put an unstamped envelope with only his name in his PO Box and when Joakim came to collect his mail in the morning, he found this mysterious envelope with just a key inside. I sent him an email from a fake email account linking to a website that I had set up. It was when the US Pitchfork site was launched so we called it Fitchpork.com and I posted the video so all he got was this key and a link to a video and he had to figure out the rest.

How important has Smalltown Supersound been? Smalltown Supersound and Joakim have been one of the main reasons that Norwegian music was recognised globally from the early 2000s because it was the only independent label that had enthusiasm, guts and a real love of music. When he wanted to start putting out music it was an easy decision to release it on Tellé Records because Mikal was genuine about his interest in music and Smalltown Supersound was an eclectic label. That’s something I value very highly. For a long period, Smalltown Supersound was the main outlet for Norwegian dance music.

These excerpts were recorded and transcribed with some parts of the interview being used in the final print of the Northern Disco Lights feature documentary film.

© Paper Vision Ltd (Pete Jenkinson/Ben Davis)

Recorded on a Zoom H2.

Transcribed by Fingertips, Louie Callegari and Tongue Tied.

Paper Vision Ltd

Paper Vision Ltd