Travelling around Norway in the Spring is a fantastic experience. During my trip in 2013, we hooked up with the key movers and shakers involved in forming the country’s house and disco scenes. I was lucky enough to touch down in Oslo, Bergen and Tromsø, and many weird and beautiful places in the surrounding areas. I travelled with Ben Davis, who was directing the film we were working on, formed from interviews with the key people from the dance scene plus Paper Recording’s label artists such as Those Norwegians. We were also curious about the country, geography, and people and how they influenced each other’s creative passions. This film had a working title of ‘Northern Disco Lights – The Rise and Rise of Norwegian House Music’. During our visit, we spoke to as many of the DJs, producers, promoters and radio stations as we could and decided to publish these best bits that sum up the trip, the film and our findings.

Joakim Haugland is the owner and has been the driving force behind the Smalltown Supersound label for over 20 years. He grew up in the small town of Flekkefjord in Norway’s south; hence his record label’s name: Smalltown Supersound. It has released music from internationally recognised artists such as Kim Hiorthøy, Jaga Jazzist, Neneh Cherry, Bruce Russell, Brian Reitzell, Kelly Lee Owens, DJ Harvey, Mats Gustafsson, Sonic Youth, Lindstrøm, Prins Thomas, Bjørn Torske and Todd Terje.

© 2014 Paper Vision Films: Joakim Haugland, Founder of Smalltown Supersound label based in Oslo, Norway.

Were you aware of when dance culture started taking off in Norway?

No, not at all. I would say because I came from indie-rock and punk, I guess. So for me, it was like SST Records, Dinosaur Jr and Sonic Youth, and of course bands like Cabaret Voltaire and Einstürzende Neubauten. When I was younger, I was listening to what was happening in England with Underworld and Orbital. I was kind of like this indie kid. I started working at the distributor Voices of Wonder in Norway and worked in their distribution warehouse for nine months. That was, I think, in the summer of 97 or 98. It was kind of like when the whole house thing blew up with Atlantic Jaxx, Glasgow underground, Paper [Recordings], Nuphonic, NRK, Soma and all these other labels. So I was kind of like putting all these records in parcels! At the warehouse, all the other guys were older than me, and they were always listening to this music. It got into my head at one point, and I brought some of the records with me at home, and I liked it. But I didn’t understand it because I was coming from this guitar world.

After a while, I started promoting Voices of Wonder [VOW] and became label manager for labels like Warp. I got really into that because going from Sonic Youth to Warp is not such a big step. From there, I went gradually more into electronic music and jazz with bands like Jaga Jazzist. All these things led me to Per Martinsen of Mental Overdrive. Via him, I met Lindstrøm when VOW was promoting the Lindstrøm and Prins Thomas album for Eskimo Recordings because we were distributing that for Norway, so I ended up managing interviews for him. We hooked up to grab a coffee, and then we started to work together. I understood that he had the same approach to his music that I had because I had never been this twelve-inch buying DJ myself. He wasn’t that much into indie music; he was more into west coast US psychedelic music from the 70s and Kraut-y stuff. But he was not from what I would call the 12” inch music from London if you know what I mean. So I think that we are more album people, you know what I mean, and I’m still that. I believe that he grew up with that art of the album himself. So I think that that was how we met musically. If you look at his discography, you can see that there are more albums than 12”s, so he is not a twelve-inch kind of guy. I would also say that my goal starting to work with him was to have him promoted into the world of Uncut, Mojo and Wire magazines. And not only take him out of the Mixmag and the DJ magazines because he is very marginal. And it stops at one point. I heard all these influences from psychedelic music, west coast, Kraut and folk music in his music. So I think there is no difference between him and Robert Wyatt. Why should they write about Robert Wyatt and not Lindstrom? They have the same kind of influences, or I feel there is the same kind of feel in the music to say something like Robert Wyatt. He’s not just playing in festivals where people are dancing on the beach and partying and stuff like that. He’s playing at music festivals together with folk and metal and hardcore, and that’s kind of where I think his music should be.

Do you see Smalltown Supersound as a label representing Norwegian dance music?

In a way, the disco and electronic scene is excellent, and the jazz scene and black metal. But outside of that, I don’t find it that interesting. In the beginning, I was kind of trying almost to hide the fact that Smalltown Supersound was a Norwegian label when I was a kid because I started the label when I was 16; it was just tape! There seemed to be an advantage coming from Norway because all the labels are from New York and London. So it was good to be from the outside. I never wanted the label to be just a dance label or only for electronic music. My ideal label would be, and this is nerdy, but like Rough Trade between 1979 and 1981, when there was Cabaret Voltaire, Robert Wyatt and stuff like Arthur Russell.

All these styles mashed up. I don’t want my label to be one sound or genre. If you are just a sound and the sound dies out, the label will die as well. That’s what we saw with labels such as Mo-Wax; when trip-hop was over, the label was over. I’m trying to have this diverse label, but I guess many people see it as a disco label, and I’ve also heard that it’s a jazz label and an indie label. It depends on what’s coming out at the time, and sometimes it’s like a lot of disco music coming out, sometimes a lot of jazz. I want there to be a real [musical] thread within the label holding it together. That’s probably the unique thing with dance music in Norway. Take a guy like Lindstrøm; he’s never listened to much dance music. He’s more into Crosby, Stills and Nash, Fleetwood Mac, psychedelic music or west coast music from the seventies. The same with Prins Thomas, who comes from a punk-rock background. I think that Smalltown Supersound reflects that. I’m from an indie background, and I release dance music, but I also release indie music and jazz.

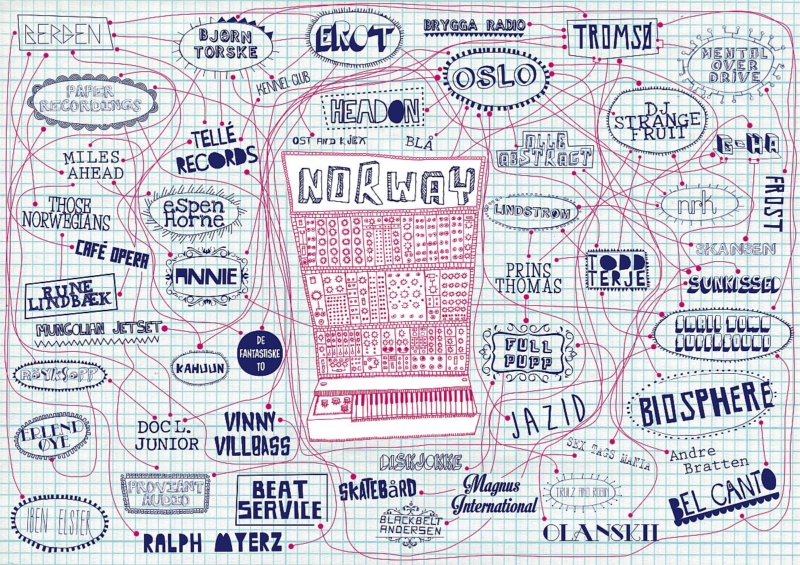

Northern Disco Lights, Family Tree poster

Do you feel Todd Terje, Lindstrom and Prins Thomas are inspired by pioneers such as Bjørn Torske and thought, “if they can do it, we can’t we do it”?

I think everybody is looking at Bjørn Torske. That’s what I have learned throughout the years; it’s like Bjørn Torske is The Godfather in a way. He was the first. What’s unique is that he lives in his ‘own’ world, so he doesn’t get influenced by trends. I’ve been record shopping with him in Chicago, and he knows exactly what he wants, totally independent of what’s happening on the scene. He’s just in a bubble. I think that’s why his music production is so unique. I don’t think there is anybody around that makes music like him. I would say that he is the pioneer. The sad thing is that he is not the most popular [internationally], but that I guess that’s the way of the world when you are a true pioneer.

Do you think that the landscape and geography influence electronic dance music in northern Norway?

It’s easier to see that from the outside, maybe, but I would say that there’s melancholy in the music. I can see that in Icelandic music, and I can see that in Swedish, and I’m Norwegian. I think it’s in all kinds of Norwegian music. I don’t believe that this style of electronic dance music could be produced in Los Angeles, where the sun is up all the time. We learn to appreciate the sun more in Norway because we don’t see the sun very often. So I think that that’s an essential element. There is a lot of rain, snow and dark season nights and days, which I believe can be found in the mood of the music.

How do you think Norwegian electronic dance music is perceived abroad?

Norwegian dance music is perceived as leftfield. I struggle to understand that because some of the music released on Smalltown Supersound is very commercial. Even when I talk to ‘club heads’ from England, they think that Lindstrøm’s ‘Way You Go’ album is too leftfield and radical. I don’t find that album radical at all; I think it’s a commercial album; however, it does have a 30-minute long track, but it’s beautiful floating music. I don’t see any leftfield elements in it at all, but maybe that’s to our advantage that we don’t know the avant-garde, leftfield style ourselves. Perhaps that’s what makes Norwegian dance music stick out from everything else?

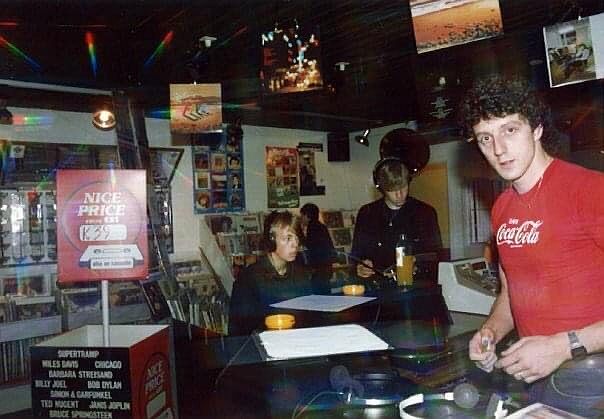

© 2014 Paper Vision Films: The Idjut Boys DJing in Oslo circa 1998

What are your memories of the Bergen Wave phenomenon?

Mikal Telle has been a friend for many years, and his label, ‘Telle Records,’ was an inspiration. I started Smalltown Supersound before him, but his Telle took off quickly. Smalltown Supersound started growing when I began releasing cassette tapes at a very young age and just learning about the business gradually as the label developed. Smalltown Supersound is a big part of my personality, and it reflects my taste in music. I was inspired by what was happening to Mikal. I don’t envy him that much that it happened so fast, but he has the best taste and is by far the best A&R manager in Norway. Telle Records is a beautiful part of Norwegian musical dance music history.

How did you find out about music, fashion and culture in Norway?

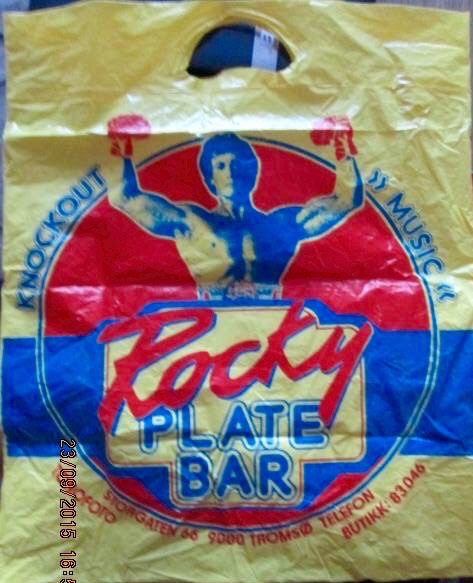

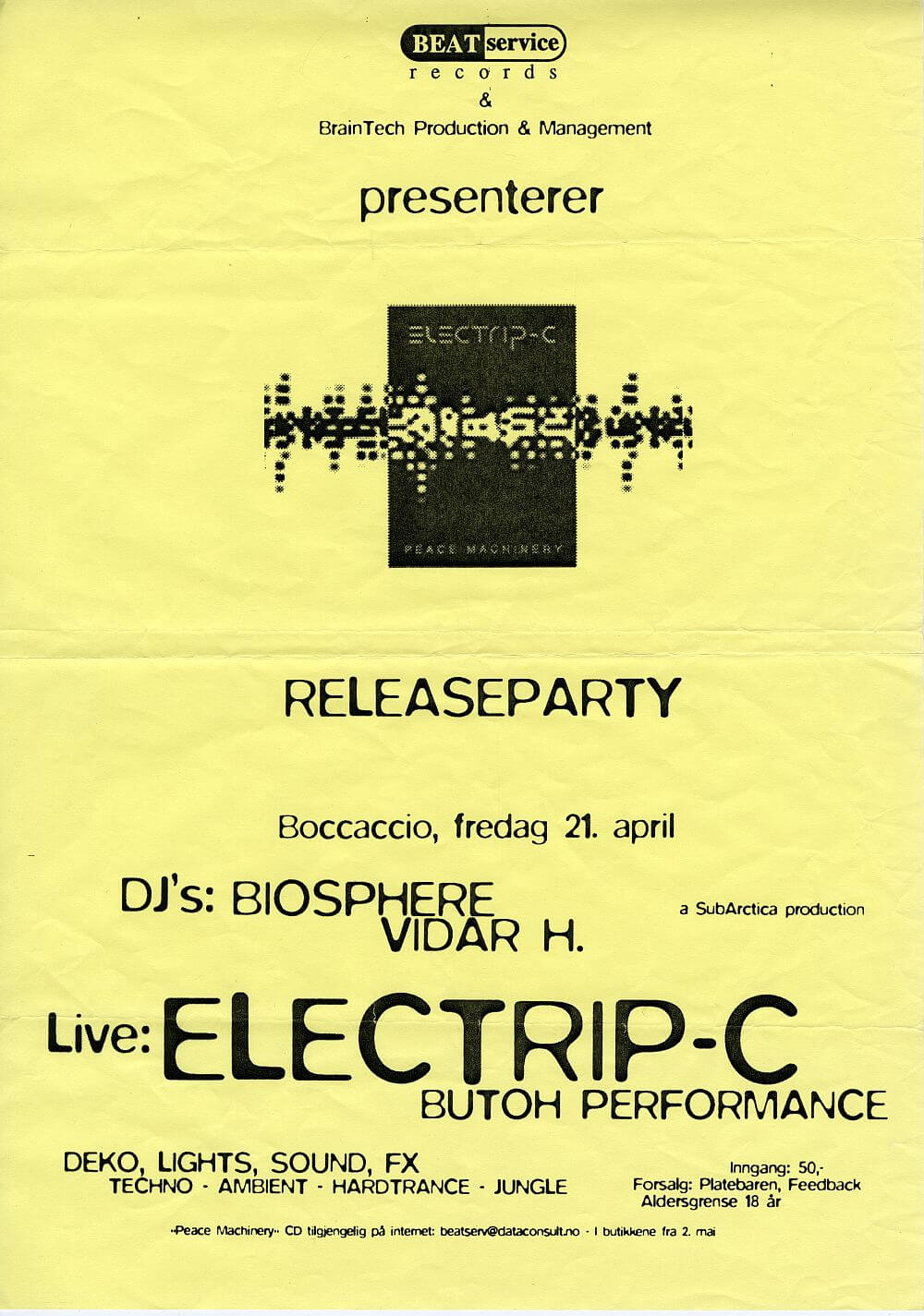

I remember reading a Norwegian magazine when I was a kid and there was an interview with Geir Jenssen [Biosphere] and Per Martinsen [Mental Overdrive]. It was inspiring for me because I lived in a tiny town without the internet. It was impossible to get movies and music, so I travelled to Oslo to buy music and cultural stuff. I began releasing music on cassette tapes and seven-inch vinyl, not knowing what a record company was! So, I read this interview with Geir and Per saying that the only thing you needed to connect with the rest of the world was a fax machine. That sounds strange now, but that’s what they were doing. They were sitting at home in Tromsø, the north of Norway, making music, sending faxes and DAT tapes to R&S Records in Brussels, Belgium. They finally got their music released on R&S Records and distributed to the world. They had international careers, and that was incredibly inspiring to me.

How do you think the producers absorbed the musical and cultural influences?

I think that Geir and Per were inspired by what was happening in the whole world. They took influences from what was happening at R&S Records in Brussels, from London and brought it all home. They absorbed it into their way of producing music, mixing it with Norwegian influences. When you listen to Bjorn Torske, there’s a lot of dub and reggae influences. I don’t know where he got it from exactly, but I think it was the record shopping trips to London and bringing the new music back into the Norwegian scene that makes the sound.

Why does Norway have such a solid connection to the disco genre?

For me, the disco connection links DJ Harvey to Idjut Boys to Bjørn Torske and Erot. If there are any connections between Erot and Bjorn Torske and DJ Harvey, there is a strong connection between the Idjut Boys and Bjørn Torske and Erot. I feel that Harvey and the Idjut Boys are from the same musical subculture that the Norwegians; they are big heroes of Bjørn Torske, Erot and the Norwegian electronic dance music scene. I don’t think there is anything already within Norwegian culture that seems ‘disco-ish. As I see it, the foundation of everything disco is Bjørn Torske and Erot, who think they were the ones who started it. Per and Geir were more into the genre of techno and ambient. Bjørn started making more techno style production, but it changed when Erot and Bjørn started making more house and disco music.

© 2010 Smalltown Supersound: Bjørn Torske, “Kokning”

How did the album with the Idjut Boys come about on Smalltown Supersound?

I felt that they were the inspiration for a lot of the artists on my label. It started when Rune Lindbæk told me about this album with the two of them, ‘Desire Lines’ by Meanderthals. It’s still one of my favourite albums in my catalogue, and it’s timeless. The Idjut Boys behave like Norwegians and have the same mood and attitude, and Dan is even married to a Norwegian. So there were all these connections to Norway, so it felt obvious to release that album. I was delighted to be working with those guys.

Why do you think that there is so much collaboration within the Norwegian electronic dance music community?

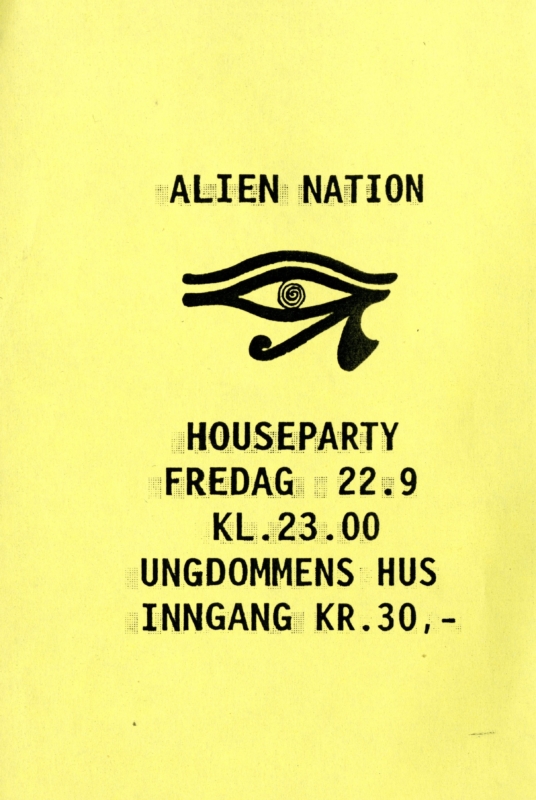

Because it’s so tiny, you’re socialising in and around clubs. In the beginning, you had Skansen, and then you had Jazid and then you had Blå. People meet at these places, and then they help and work with each other with the business aspects, the remixes or production. It is so much more significant in London, and I wouldn’t know where to meet these kinds of people, here it’s straightforward. I think it’s also part of the scene’s success because everybody is collaborating, helping and inspiring each other. They are doing it together and sticking together.

Is there competition between the artists in the electronic dance music community?

There is healthy competition as everybody is passionate about being as good as their friends and fellow producers and DJs to become as good as their neighbour. So if you see, some of these people have studios very close to each other and stuff, but I think it’s healthy. I don’t believe that the producers and DJs are wealthy but have been DJs the whole time during their production careers; I guess that’s the business of DJing; it’s the same the world over. But, of course, Norway is an excellent country to live in, and it might have influenced the ability of these guys to produce and buy new music and how they consumed the culture around them.

Do you think the different cities and locations can have different sounds?

I don’t know. There are not so many people in Bergen except for Bjørn and Röyksopp doing this kind of music. They became superstars in that kind of music and went on to make other music. I don’t feel like they are part of this scene at all if it is a scene. I think that Bjørn is in his creative world. He’s kind of in this bubble. I believe that Oslo is the principal city for dance music at the moment. Some of the most recognised producers like Röyksopp, Geir Jenssen and Bjørn Torske came from Tromsø but don’t live there nowadays apart from Per Martinsen!

Do you think the landscape in Tromsø has had an effect on the music from there?

For Biosphere, obviously, it had, because of this kind of cold, ambient thing. I’d also say it for the cold techno music. So it’s pretty weird that they are making warm house and disco music because it has nothing to do with the ice-cold and nature you see in Tromsø. So maybe the answer to your question is that all these people moved from Tromsø to Bergen.

How did you hook up with Todd Terje?

He works in a neighbouring studio of Lindstrom and Prins Thomas, and I knew him through friends. Since the start, he’s been part of the scene, and everyone knows everybody as it’s so tiny! I was surprised by the success of Todd’s ‘Inspector Norse’ in many ways because it was a beautiful thing that happened without us spending a lot of money to make it happen. It became massive with just word of mouth. Just the way we wanted it. It was just Terje, and I am doing all the work on our own. I’ve never experienced anything like it before. It was making such a global impact without a budget and just the two of us doing the promotion. It is an EP, it’s not an album, and EPs are harder to promote because you don’t get all the reviews that you usually get in the big broadsheets and music magazines. It was a long process, but because it is such a great track, people started to talk about it, and then it happened, blew up. It is a lovely process to witness. Todd Terje is from the dance world, so I don’t think that albums inspire him in the same way that Lindstrøm has been. As a DJ, he knows what works on the dancefloor and makes dancers feet move. I guess this is similar to Prins Thomas, as he comes from a punk-rock background.

© 2015/2001 Smalltown Supersound/Tellé: Bjørn Torske, “Trøbbel”

Do you think the success of these artists (Röyksopp, Todd Terje, Lindstrøm) has now made it easier for Norwegian artists to be successful internationally?

I would hope that Bjørn Torske and Mungolian Jetset [Pål “Strangefruit” Nyhus and Knut Sævik] could be famous as well, but it’s those three who get the headlines. I would say that Bjørn Torske is out on his own, and that’s what makes him so unique.

What do you see as the future of Norwegian dance music?

Some younger producers make this kind of music, but I feel you need life experience and an extensive record collection to produce the sound they create because it’s an advanced, complex style of music. It’s light-years away from what I would call ‘head banger’ kind of music. There’s no fuss and turning the volume up to 11. The music is not just about dropping ecstasy and dancing. I think that this scene is accidental. Behind it are many years of DJing, playing in bands, and developing an extensive record collection! To use a football analogy, the goalkeeper always get better the older they get, between 30 to 36 years old. It’s a peculiar thing. The rest of the team is peaking, maybe 24 or 25, so the disco scene is more like the goalkeepers; they are getting better the older they become. So I think there is a bright future for these guys like Todd Terje, Hans Peter Lindstrøm, and Prins Thomas because I don’t think age will influence their music production careers. You can see with the Idjut Boys and DJ Harvey; they get better and better. So I don’t think it’s true that you are too old to play or produce this dance music. On the contrary, I believe that the older you are, the better you become!

Do you feel supported by the Norwegian media?

It’s an underground scene, but I would say as the journalists are really supportive, the artists get good reviews and press coverage. When I started to promote Lindstrøm’s album at VOW, we told the most influential press and media that he was remixing Madonna to encourage them to write about him; it worked! I had to use a little trick to get the press to write about the album. It seems easier nowadays because Norway is perceived as an ‘underdog’ type of country punching above its weight. Our population is only 5 million, so every time a Norwegian does anything ‘good’, even in chess or in football, you get a lot of attention. Even more so with music. So if you get attention abroad, you will get attention at home. That’s how it works.

What is your favourite Norwegian record?

Biosphere’s ‘Patashnik’ album meant a lot to me when I was young. It was produced early in Norway’s dance music history; he was Norwegian, and it had a Norwegian sound. It sounded like he was part of the same world as Aphex Twin, The Orb, Orbital and Underworld. If I had to choose a single track, it would be ‘I Feel Space’ by Hans Peter Lindstrøm because the tune has been so influential. It’s like a classical composition.

Who is your favourite Norwegian producer?

Bjørn Torske has been there from the very beginning, and Lindstrøm because he keeps on producing new music and is evolving the whole time. He always takes it to the next step so that none of his production ever sound the same. So I think that in 10, 15, 20 years, you will be able to look back and see a coherent thread through his music but with a good dose of diversity.

Your favourite Norwegian club?

That’s easy, Blå from 1999 to 2005. It was primarily a jazz club. Sunkissed DJs (Geir Aspenes and Olanskii), Prins Thomas, Pål “Strangefruit”, and Todd Terje had their club nights there. It was the most happening place after, first you had Skansen, then you had Jazid. I went to both Skansen and Jazid a few times. But I was mostly hanging out here in this venue when it was called ‘So What’. When this club shut down in 1999 or 2000, I moved over to Blå. From 99 to 2005, when they changed owners was magic years where it was a mixture of jazz, avant-garde music, indie-rock and club music. I think that that’s also the core of the scene because, at this club, you could have a free jazz concert on a Friday night from 9 to 11, and then you could have like a Prins Thomas club night right after. So you could go from Arthur Doyle free jazz, crazy set, right over to a Prins Thomas set. And to be honest, there’s a lot of similarities between Arthur Doyle and Prins Thomas. But it seemed crazy on the paper, but when you were there, it was all mixing beautifully. And that is why Blå is such a special place because it was not a pure dance place like Skansen, Jazid, as you can hear in name, it was more like a jazzy electronic place. Skansen was a dance place. But Blå was this mixture of genres, but mostly a jazz and dance club space where you could also have noise, hardcore, and all kinds of underground sounds. And everybody met there, a lot of music, musicians and producers mixed at Blå from 98 to 2005 when they had their best years. Blå was very influential for both my artists and label for both the jazz and electronic side. Again, it was about tearing down the walls between genres.

© 2014 – Paper Vision Ltd (Pete Jenkinson/Ben Davis)

Recorded on a Zoom H2.

Transcribed by Fingertips, Louie Callegari and Tongue Tied.

Geir Jenssen’s Biosphere is classic.

Geir Jenssen’s Biosphere is classic.